A recent study found that construction and operation of wind farms causes soil drying and significantly reduces soil moisture content, particularly on the downwind side of turbines.

As drought continues to be a major concern for Iowa’s 2023 corn and soybean crop, one would think that the last thing we’d want to do is reduce our soil moisture content even further. But a recent study conducted by the School of Resources and Environmental Engineering at Ludong University in China found that the operation of wind farms does just that. Using data from the Landsat 8 and Landsat 9 satellites combined with data gathered from local meteorological stations, researchers Gang Wang, Guoqing Li, and Zhe Liu studied the soil moisture of grasslands before and after wind farm construction at five different locations in Inner Mongolia. The results? The soil moisture content was significantly reduced once the wind turbines went into operation. And this soil drying was not limited to just the land that the wind turbines were located on. Significant soil moisture reductions were found up to 20 miles (30 km) away from the turbines as shown in the following chart:

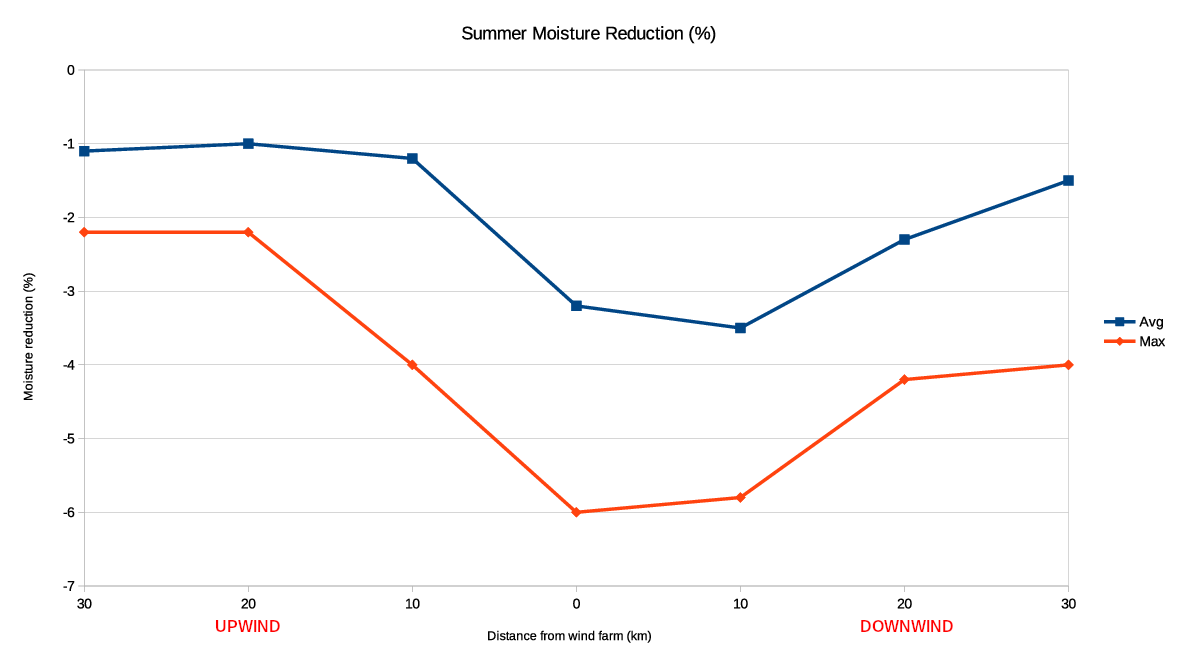

This chart shows the average and maximum moisture reductions for the summer (the season when maximum drying occurred) after wind turbines went into operation. The left side of the chart shows the upwind side of the turbines and the right side shows the downwind side. As the chart shows, moisture reductions caused by wind turbines occurred on both the upwind side and the downwind side of the turbines, but were most pronounced on the downwind side, with a maximum of nearly 6% reduction in moisture at a distance of 10 km (6.2 miles) from the turbines.

One particularly disturbing aspect of this chart is that if you look at the average reduction (the blue line with the square points), you will notice that the soil drying is actually worse at a distance of 10 km downwind from the turbines than it is at a distance of 0 km. This means that farmers downwind of the wind turbines will actually suffer more severe soil moisture loss than even the farmers who have signed contracts to have wind turbines on their own fields.

Once again, landowners who want wind turbines on their fields continue to insist this is a land rights issue, and again, they are partially correct. But land rights don’t apply only to farmers who want to put 560+ foot tall skyscrapers on their fields. Other farmers who live downwind of them also have rights. And one of the basic tenants of land owner rights is, and has been since at least ancient Roman times, that one farmer does not have the right to do something with their land that is going to ruin the land of neighboring farmers.

Iowa has already been facing increasingly common droughts in recent years that have threatened corn and soybean harvests. Do we really want to invite something into our farm lands that is going to dry out our soils even more? This is not about green energy, or producing electricity that Iowa doesn’t even need. It’s about preserving and protecting our way of life.

Source: Wang, Gang; Li, Guoqing; Liu, Zhe. (2023) “Wind farms dry surface soil in temporal and spatial variation.” MethodsX, Vol #10. 10200.

First we had wind turbine fires causing destruction to neighboring farmland; now we have another way to do it. Let’s just dry out the neighbor’s land so the crops can’t grow. Just another example of the many problems associated with wind turbines.